Why can the inherent emptiness of everything solve anything, least of all the problem of suffering?

To see how this you have to have suffered and perceived how that suffering is a consequence of the holding of fixed ideas, attitudes, attachments and the belief that things must be one way

Powerful, lucid prose on the profound roots of our suffering in our attachment to our ‘views’ — that “things must be one way or another or life would not be worth living”:

… to see why the inherent emptiness of everything can solve anything, [most] of all the problem of suffering … you have to have suffered and perceived how that suffering is a consequence of the holding of fixed ideas, attitudes, attachments and the belief that things must be one way or another or life would not be worth living.

We acquire the social stances of our teachers and parents and the culture into which we are bom and culture is itself a complex patterning of ideas, explanations and values. These become the cages within which we suffer, cages made of presuppositions and presumptions.

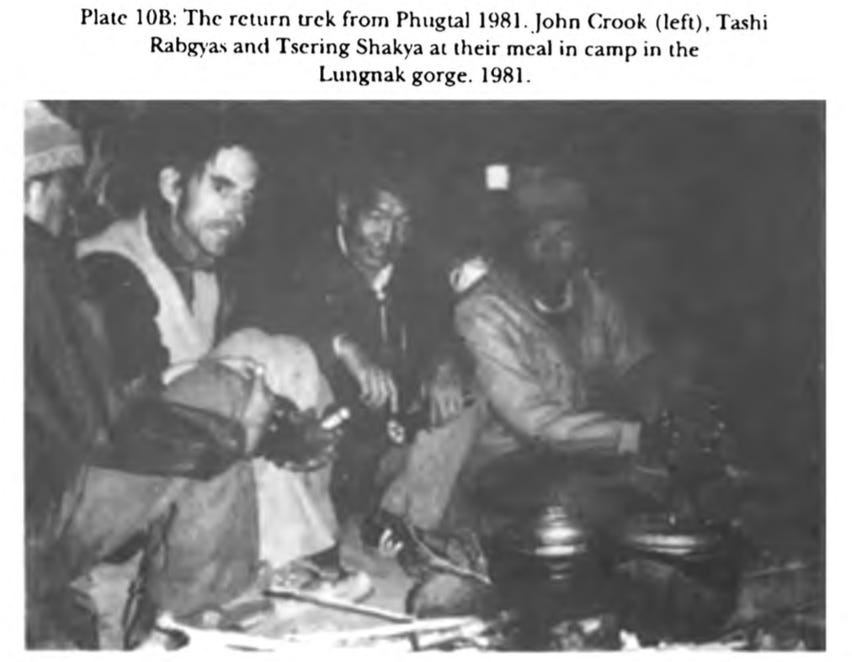

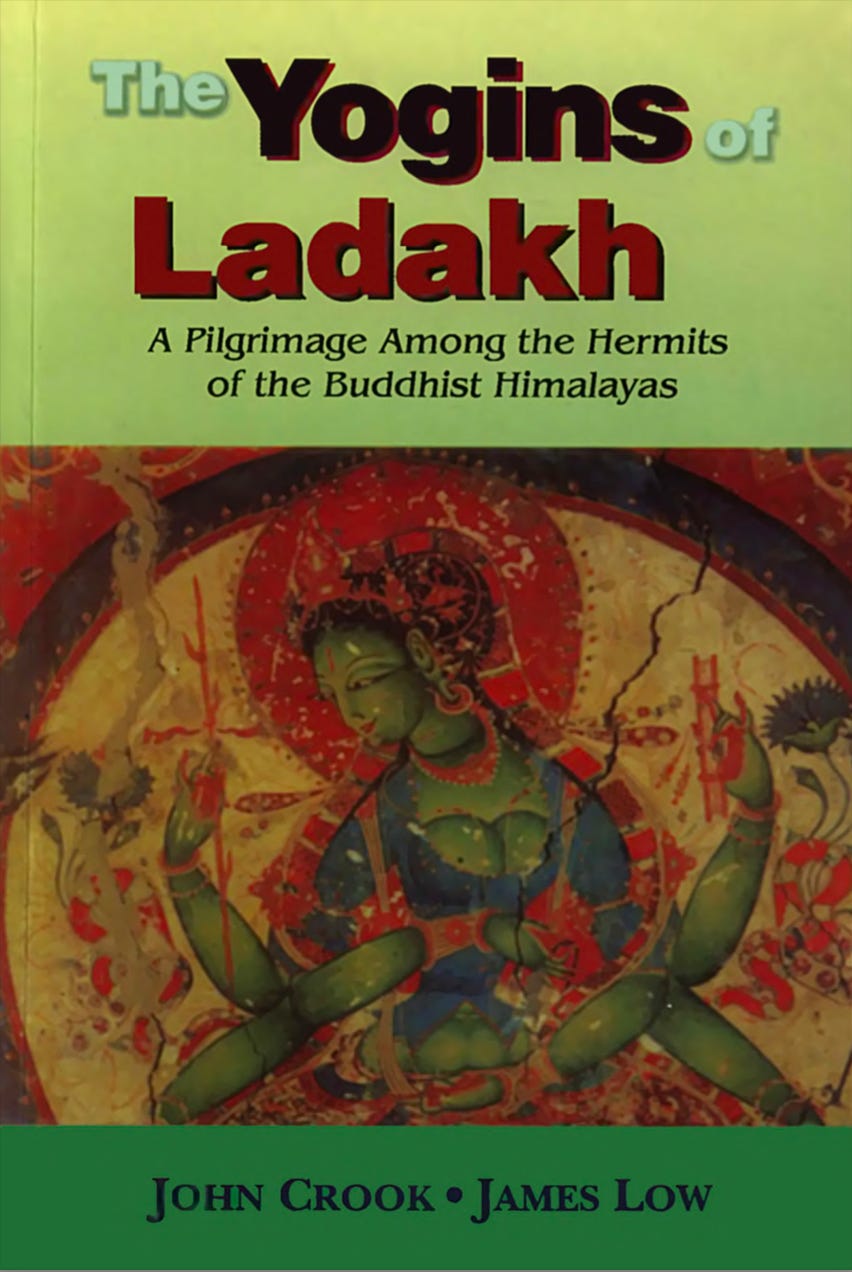

This comese from the Yogins of Ladakh by the late John Crook and James Low, which I came across pretty much by accident whilst browsing students of Sheng Yen — it turns out Crook was his first western Dharma heir and after a first career as an ethologist.

Full excerpt

The methods of Nagarjuna, brilliantly developed by Chandrakirti, swept aside all alternative views and remain even today the ultimate Mahayana philosophical position. It is important to note that it asserts neither the existence of a void as a basis nor any kind of permanent principle such as the atman of the Hindus. What it does do is to take the thinker along a line of thought that eventually drops him into a condition where no further thought is possible. The opponent drops his position and thereby his attachment to it. Essentially it consists in the undoing of the reifications natural to linguistic expression. There is an experiential component to such a process which can become the realisation of clear conceptless being. Gelugpa monks, who are especially keen on this approach, therefore use verbal debate and a form of meditation that uses probing intellectual analysis, both leading to this end. 8

It is not easy however to convey this enthusiasm to another, because initially it is difficult to see why the inherent emptiness of everything can solve anything, least of all the problem of suffering. To see how this can be, you have to have suffered and perceived how that suffering is a consequence of the holding of fixed ideas, attitudes, attachments and the belief that things must be one way or another or life would not be worth living. We acquire the social stances of our teachers and parents and the culture into which we are bom and culture is itself a complex patterning of ideas, explanations and values. These become the cages within which we suffer, cages made of presuppositions and presumptions. Conventional vision is a result of socialisation and the Madhyamaka view pushes us towards the limit of what it can sustain. When we reach that point, we stand intellectually naked in a universe about which no assertion can be made.